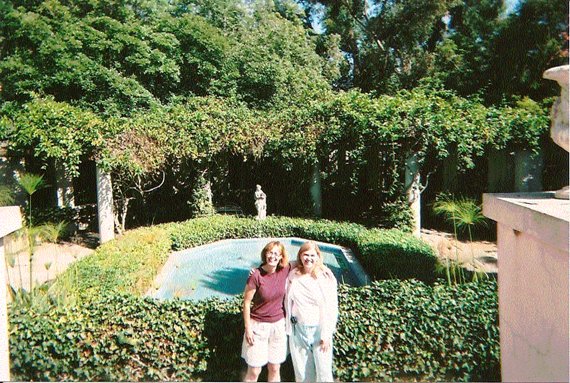

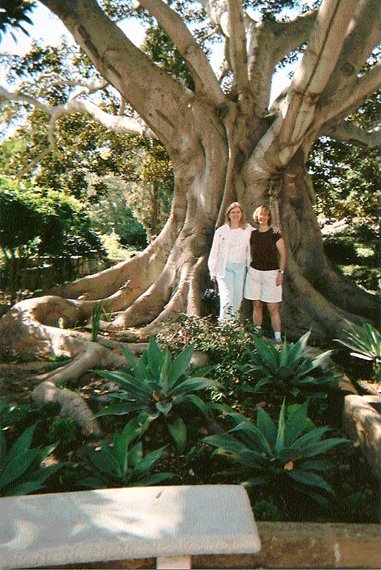

I was so excited!! I had been accepted by the famous Mitchell Lurie for summer music camp! I had never been so far from home, but away I went, that summer of 1972, down to Santa Barbara. The Music Academy of the West, located on the bequeathed estate of the famed opera singer Lotte Lehmann, must be one of the most beautiful places on God’s green earth, with its sculpted gardens, century- old trees, fountains, and old Spanish-style buildings.

I remember sitting-in on vocal coachings given by Marcial Singher, accompanied by the equally legendary Gwendolyn Koldofsky, whose Schubert sounded like auditory velvet. Reginald Stewart played an all-Chopin faculty recital, epitomizing tasteful rubato. Jerome Lowenthal was the electric soloist in Gershwin’s exciting Concerto in F. Maurice Abravanel, then music director of the Utah Symphony, was the elegant and cheerful conductor of the Festival Orchestra. I remember one rehearsal of this fine group, with young musicians from all over the U.S., when the aging maestro with his sparkling blue eyes had us all in contortions of laughter: he corrected a player’s posture by saying, in this thick French accent, “Nothing creative was ever done with one’s legs crossed.”

The faculty was excellent, not only for their musical prowess, but also for their skills in working with young people. The marvelous cellist Gabor Rejto was my chamber music coach for Prokofiev’s difficult Quintet for oboe, clarinet, violin, viola and double bass. When the performance didn’t go as well as I had hoped, and I was near tears, he laughed and in his charming Hungarian accent said, “But Kathy, don’t you know that in concerts the notes move up and down on the page?”

Then there was Mitchell Lurie, always patient, always kind, and always demanding excellence as he lighted the way for us. A group of us drove down to Claremont College to hear a chamber music concert at a festival there in which he, French horn Barry Tuckwell, cellist Joel Krosnick and others played the Schubert Octet.

That was it.

That performance, July 26, 1972, was a turning point in my life. I had never heard such beautiful clarinet playing, and with no big outward show. Mitchell Lurie spun the gorgeous melodies up into the air and the web woven that night between him and the other seven was heavenly.

After that concert I knew what I wanted to do with my life—play the clarinet. I had always feared “I wasn’t good enough.” Lurie dispatched with that with his philosophy of “You be the best YOU can be.” Complaints that things were hard met with “Who asked you to play the clarinet?” I groused about reeds and he said he had a solution for me. I thought he was going to offer me a tour of his reed factory, but, no, he said, “Play the flute.” I was scared of something and he recounted his mother’s words when he didn’t want to do something: “Well, you just go back to bed and pull the covers up over your head and stay there all day.” There were no stones to hide under in his studio. You got used to dropping your whining, and just sitting down to do the work. He always slowed you down to do things right, with kind, yet firm words.

I had a great summer, and returned to Washington to start my third year of my bachelor’s degree.

After the Mitchell Lurie Tribute Concert held at the University of Southern California on September 6, 2009, my clarinetist friend Patty and her bassoonist husband, Duncan Massey, took me on a nostalgic trip up to the Music Academy, which they had both also attended. It was my first time back there since 1973. As we gazed over the manicured grounds I said to her, “No wonder I wanted to become a musician—I thought it was going to be like this!”