Going back to work in Puerto Rico in August was starting to feel like the normal thing to do. As classes resumed at the Conservatory on the 14th I was preparing to leave my little house two blocks away and move to an apartment over on the beach. I found a 15th-floor, two-bedroom rental for the reasonable price of $400 per month. It was a little cheaper than the going rate because it had just been vacated and needed some work. Our realtor had been told “Don’t even show it to an American,” because it was in such bad shape. But she got me an appointment to see it, and I perceived those walls that needed painting as a great opportunity to grab the place cheap, with an offer to fix it up ourselves.

The view was spectacular—the ocean and beach to the north, a cemetery next door to the east (quiet neighbors!) with El Yunque (the highest peak in the rainforest) looming farther out to the east, and the lagoon to the south.

September 1st was move-in date. My new roommate, Alice Connolly, a cellist from San Diego, and I went over to paint, borrowing rollers and drop cloths from the real estate agent. I was intent on returning them on the 1st, and tried to do so during morning rush hour, before I understood the traffic patterns of the area. I ended up crashing my car into an oncoming car ½ block from the apartment!@#$%^&*()_+>?” If I hadn’t had my seat belt on my embouchure would have been seriously altered. I was suddenly very grateful that I hadn’t killed or injured anyone. I keep the lesson of “slow down and look all ways before you turn” with me to this day, along with a realization that driving is the most dangerous thing we do each day.

September 5th was the first rehearsal of the PRSO season. We had a new music director—Sydney Harth. Things didn’t start out too smoothly. One Saturday was scheduled for two, hour-long educational concerts scheduled back-to-back with ½ hour between, followed by an hour break and then a two-and-a-half hour rehearsal. Harth understood a service to be a total of 2 ½ hours, and the master agreement allowed two services on Saturdays. However, the exact wording of the contract was that a service was a rehearsal or a concert, not to exceed 2 ½ hours.

So when the day arrived, the orchestra grumbled mightily, and when presented with the printed reality, Harth replied that if he had to eliminate something, he needed the rehearsal more than the second concert. The Orchestra met after the first concert and took matters into its own hands: “Our people are arriving for the second concert, and we are going to play for them.” So we did. Harth had gone home. Our concertmaster, the consummate musician and great gentleman José (Pepito) Figueroa, gave upbeats with his bow and we did just fine. Our public was greatly pleased. On the island there is a very strong understanding that our job in the Orquesta Sinfónica de Puerto Rico, which is supported by local tax dollars, is to play for our people (nuestra gente.)

Outside gigs that fall included a Shepherd on the Rock with visiting pianist/soprano team Eckhart and Kay Selheim, a Bartok Contrasts with Henry Hutchinson, Jr. (who is now our concertmaster) and his mother, Luz, and a Dumbarton Oaks in a modern music festival. Pro Arte Musical brought in Maestro Eugenio Marco to conduct a concert with José Carreras and Katia Ricciarelli. PRSO guest conductors included Luis Herrera de la Fuente, Henry Temkin, Emerson Buckley, Genesio Riboldi, Jacques Brourman, and Boris Brott, among others. Yefim Bronfman was one of our soloists.

Meanwhile, my personal life was taking on new dimensions. There was an opening in the cello section; my father, W. Howard Jones, had just retired from his position as professor of cello at the University of Idaho. After my parents divorced (when I was in fourth grade) I had always felt a big void where my father had been, so I figured this might be a chance to get to know him again. Dad came down and auditioned for Harth and began to play in the orchestra in October. He moved into the little house that I had moved out of, which was still occupied by my now ex-boyfriend. I don’t know what possessed me to think that would be a viable arrangement. Well, it certainly wasn’t. I started getting calls from one complaining about the outrageous behavior of the other, then the tables would turn and I got the second phone call from the latter complaining about the former. After a month of trying to be peacemaker and referee, I strongly urged my dad to find his own place. He finally did, luckily finding an available lower floor of a house even closer to the Conservatory. Whew, I was so relieved to get those two guys into separate spaces!

At the Conservatory there were storm clouds also. Rules said that tenure could be given after three years of successful teaching, and I received a letter granting me tenure. I was thrilled! Several weeks later I found out from the Dean that some of my students had come to him threatening to drop my class when they learned of the granting of my tenure. In fact, some of them did drop. It was a time when the independence movement was strong, and some felt that an outsider shouldn’t have permanence. Although it was uncomfortable, I weathered the storm.

We arrived at Christmas time and enjoyed some wonderful parties. Dad and I went to the Figueroa house one evening for a party and were there when the “parranda” arrived—a group of musical friends dropping by, singing, playing and expecting to be fed and given drink. Pepito’s sisters Carmelina and Angelina had prepared gallons of food and a jolly time was had by all. The parrandas are a wonderful Christmas tradition in Puerto Rico.

There was a special orchestra concert scheduled for January 4th at El Morro (the magnificent 17th Century Spanish fort in Old San Juan.) It was a blustery day; in the area where we were to play, the music stands were blowing over, and one folder of music flew over the ancient walls and out to sea. Dad had arrived early, and was counting the stands blow over, concerned for the safety of his cello. He was playing an expensive Guarnarius, which he had taken in on trade when he had sold his even better Guarnarius to Joel Krosnick of the Juilliard Quartet some months before. While the rest of us were waiting for management to make a decision whether or not to cancel the concert, my dad, a World War II veteran, made up his own mind, packed up and headed out of the fort. The Minister of Culture was walking in as Dad was walking out, and stopped to beg him to return and play this very special concert. My dad replied, “I counted five stands blow over. My cello is worth $150,000. If it is damaged will you take responsibility?” “Oh, no,” replied the Minister. “But you expect me to? Horsesh__!” Daaaaaaaaaaaad….. Finally the concert was cancelled. Dad was long gone.

We played a concert in the town of Coamo, and I scheduled the trip so I could take Dad to the “Baños de Coamo,” a “parador” (country inn) at the site of some natural hot springs. In January the pool with the hot mineral water is really paradise!

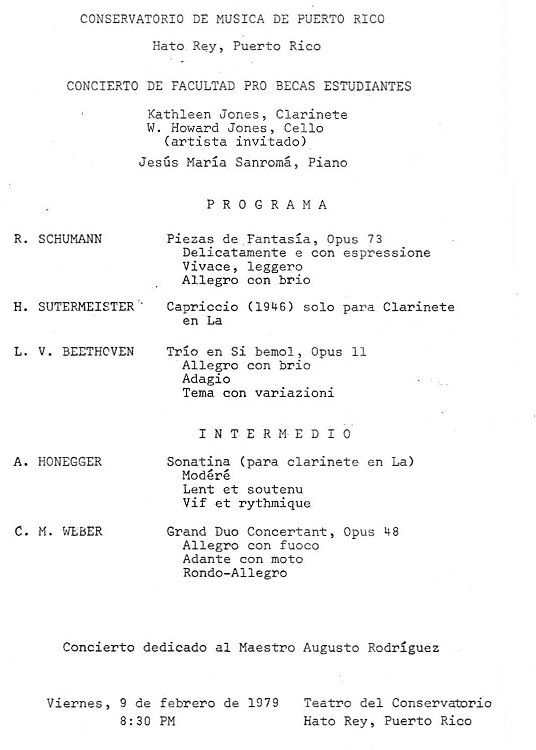

We played a concert in St. Thomas in February to inaugurate the Reichhold Center, the new amphitheater at the College of the Virgin Islands. We played with singers Carol Neblett and Justino Diaz for Pro Arte. We did the Beethoven Violin Concerto with Sydney Harth as soloist and conductor—that took some serious listening to hold together without the comfort of a baton up front. I played a recital with the legendary pianist Jesús María Sanromá and my dad on February 9th.

A friend of Dad’s from Washington State come to visit, so I called the Arecibo Observatory to see if we could go see the giant radio telescope. I spoke to the fellow in charge of public relations, who turned out to have graduated from the same university as my oldest sister. When we went out to see the facility he gave us the grand tour, even letting us climb up the ladder to stand on the platform in the middle of the dish. I remember his words as I was ascending—“You’re about to know what it feels like to be a drop of oil in a salad bowl.” Indeed! One step later I was in the middle of a 1,000-foot-in- diameter dish of metal panels, with the telescope’s arm suspended above. It was an unforgettable moment! The Arecibo telescope, located an hour and a half from San Juan in a “karst” (limestone) sinkhole, has been the site of some exciting astronomical discoveries while managed by Cornell University, and hopefully will continue to be so under the new management consortium.

The violist Donald McInnes visited as soloist, as did pianist Lazar Berman. Guest conductors included the Nicaraguan Jorge Sarmientos, George Trautwein and Maestro Izquierdo.

Meanwhile, there were mounting troubles in the offices of the Casals Festival. The clarinetist who had told me he had no interest in the clarinet when I arrived in 1975 was letting the Festival staff know that he WAS interested in playing principal clarinet in the Casals Festival. Evidently he was pressuring, based on the precedent that I had played principal, substituting for Michelle Zukofsky in 1977. The music director at the time was Jorge Mester, who agreed to hold a local audition for the chair. Four of us local clarinetists played in the audition, which was held on Dec. 20th (1978.) Mester, the only judge of the screened audition, eliminated two and asked the conductor/clarinetist and myself to play again. Then he met with each of us separately in the Festival office, explaining that he wanted the two of us to share the first and second chairs in the upcoming Casals Festival, and at the end he would decide who had done the better job in the orchestra. I said that although I wasn’t thrilled with the situation, I would agree, because it seemed ultimately fair. Mester told me that the other finalist hadn’t agreed to the terms; he told him when he was leaving and suggested he reconsider, giving him his phone numbers. Mester told me that if he didn’t hear from the conductor/clarinetist before he left the job was mine.

A few days later my phone rang—“Kathy, this is Jorge Mester. My flight is leaving and Mr. ____ didn’t call me—the job is yours.” Well, okay.

I was looking forward to playing in that great orchestra again!! Then, on May 18th, the Puerto Rico Symphony musicians didn’t come to terms about salary for the weeks of the Festival, and management cancelled the venerable event–completely. The 1979 Casals Festival didn’t happen. I was sorely disappointed!

It was a busy summer though: I played the Bartok Contrasts at the Marcellus Master Classes at Northwestern on June 28th, with pianist Chris Severin, and then-violinist Charlie Pikler (who is now principal violist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra!) We cooked!

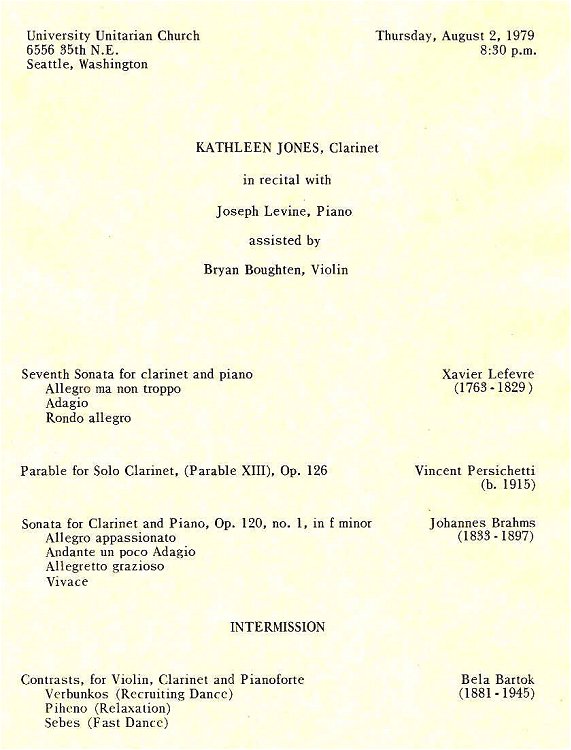

Out in Seattle I heard the Philadelphia String Quartet do a complete Beethoven cycle—wonderful!—and saw The Valkyries at Seattle Opera. I went hiking to Dishpan Gap with my sister Evie, and gave a recital with Joseph Levine and Bryan Boughten at University Unitarian Church on August 2nd.

I returned to San Juan in time to hear the accomplished brother/sister duo of Yvonne and Guillermo Figueroa play chamber music on August 12th and 19th. There was lots of music to play and hear!