So, here I was, living in San Juan near the Conservatory, renting a little house that was not plumbed for hot water. My life was packed with new experiences: learning Spanish, beginning to assimilate a new culture, growing into a principal chair woodwind in a symphony, and teaching in a Conservatory. There were also tremendous tensions, and even a court case to come. This first year was offered to me because of the recommendation of a highly esteemed musician; after that, my employment was based directly on my work, and it was not always an easy path.

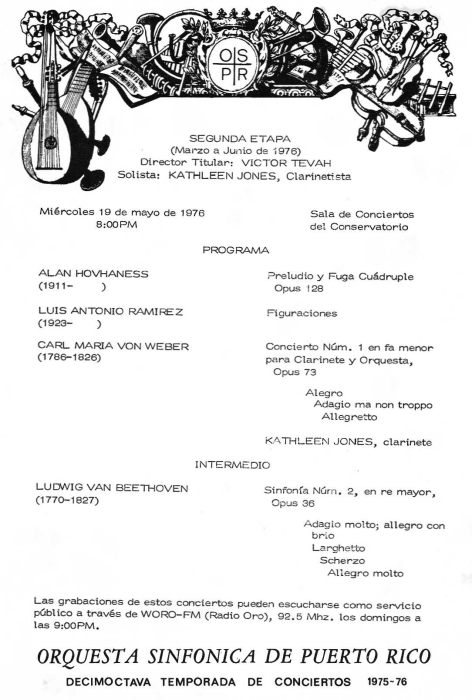

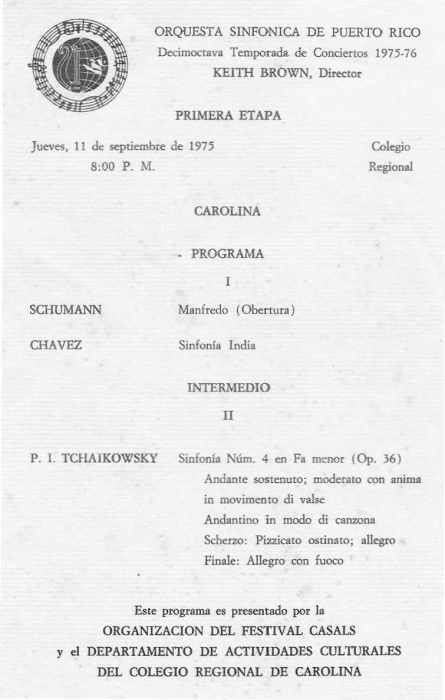

There was lots of playing to do. My first concert was a run-out, September 11, 1975, with famed trombonist Keith Brown conducting Schumann’s Manfred Overture, Chavez’ Sinfonía India, and Tchaikowsky #4. We repeated the concert at the Conservatory at 11 a.m. on Sunday the 14thv, with Ravel’s Tziganne and the Chausson Poeme with violinist Yosef Yankelev instead of the Schumann. We started 45 minutes late to accommodate the line for tickets—it was the first time that admission had been charged ($3.00, $2.00 or $1.00.) When Casals was alive the OSPR concerts had been free.

In the end of September, guest conductor Eve Queler led us in Freischütz Overture, Beethoven’s 7th, arias with bass Daniel Bonilla, and the Firebird. In early October Argentina’s Simon Blech conducted Beethoven Coriolanus Overture, the Brahms Double with the Odnoposoff brothers, Camps’ Viñetas Porteñas, and Hindemith’s Mathis der Maler. At one point in rehearsals Blech addressed me saying, “Excuse me, but you’re playing like a girl.” Believe me, next time through, he got the passage loud and accented, and he was happy. He stayed another two weeks, and our next concerts with him included Rachmaninoff’s 3rd Piano Concerto with Spaniard Joaquin Achucarro, and Dvorak’s 8th.

Then arrived our Music Director, Victor Tevah, a Chilean. The orchestra really liked him, for his amiable manner, and also because of his fine musicianship. In late October we played Beethoven’s 1st, Koussevitsky’s Doublebass Concerto with soloist Federico Silva, Bizet’s L’Arlesienne Suite #1 and Wagner’s Tannhäuser Overture. He stayed until December leading us in concerts including Gershwin arias from Porgy and Bess with Abraham Lind Oquendo, Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony, Ippolitov-Ivanov’s Caucasian Sketches, Glinka’s Ruslan and Ludmila Overture, Brahms 1st Symphony, and, bless it, the 1812 Overture, among other things.

The PRSO season was divided into two parts: 14 weeks before Christmas (September to December,) and 14 weeks after (March to June.) That left some prime tourist season weeks for the musicians to play other jobs, especially in hotels. In January of 1976, the Arturo Somohano pops orchestra (using mostly PRSO musicians) was used for a gala concert at the University of Puerto Rico Theater to benefit the beautiful art museum in Ponce. The soloist, playing Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto, was former Puerto Rican Governor the Honorable Luis A. Ferré, for whom our performing arts center is now named.

I was beginning to see that music in Puerto Rico was taken seriously. There were whispers that I had to practice—like that was something bad. The truth had two parts to it: your first year sitting in a principal chair there is lots to learn, and you’d better figure it out–fast! And, the music schools in Puerto Rico use the Spanish solfege system as part of theory training, resulting in tremendous sight-readers. I had studied one year of “moveable do” in college. After working with those who have studied two or more years of “fixed do,” I can attest to this system’s great advantage: you see it on the page, and you hear it in your head.

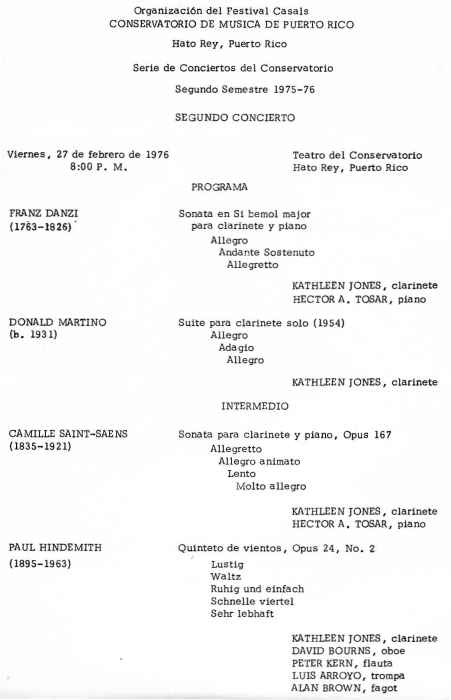

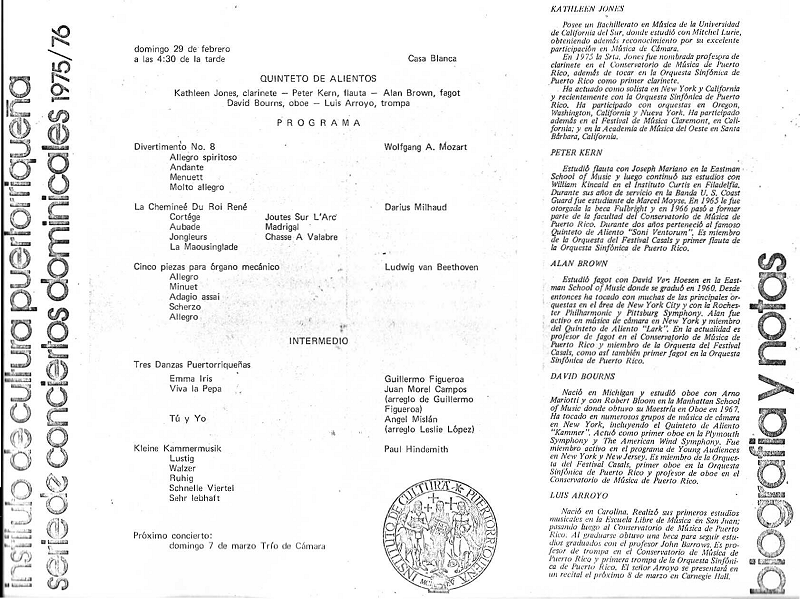

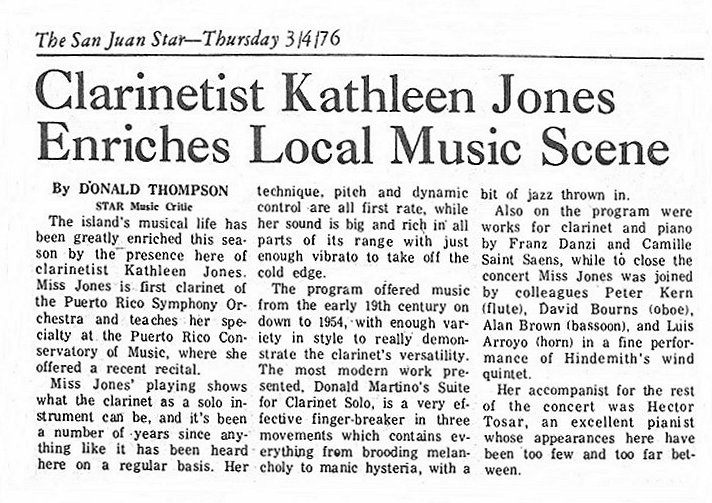

My first opera was La Boheme in February at the University of Puerto Rico Theater, with the fabulous Italian maestro Anton Guadagno conducting, and voices on stage including Pablo Elvira, Maralin Niska, Jaime Aragall, Justino Diaz, and Olga Iglesias. I gave a recital a couple weeks later at the Conservatory—Danzi Sonata, Martino Set, Saint-Saens Sonata, and the Hindemith Woodwind Quintet with my fellow principals from the PRSO. Two days later we gave a full quintet concert (Mozart, Milhaud, Beethoven, Hindemith and local “danzas”) at the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture.

Then the PRSO season resumed and brought Beethoven’s Fidelio Overture, Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Tchaikowsky’s Piano Concerto and Sibelius 1st. Sandwiched around guest conductor Mark Cleghorn’s concerts (March 18th in Aguadilla and March 21st at 11 a.m. at the Conservatory) were two full length performances of Verdi’s opera Otello, conducted by Joseph Lliso at the UPR Theater, March 19th and 21st. I remember rehearsing until midnight, and racing off from one commitment to another without time to eat. Mr. McColl always said that musicians are either overworked or unemployed. It sure felt like the former, and I was grateful!

There were zarzuelas to play (like Spanish operettas,) with parts that looked like they were copied by chickens with ink on their feet running across manuscript paper. PRSO concerts included Tchaikowsky 6th with Spain’s Odon Alonso; Mendelssohn’s Scotch with Uruguay’s Hector Tosar; and then, with Tevah, Fingal’s Cave, El Amor Brujo, Schubert’s Unfinished, Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, Beethoven’s 2nd; Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain, with Judith James, and, oh yeah, Weber’s First Clarinet Concerto, with Kathleen Jones.

The soloist for the May 19th concert cancelled about four weeks prior. I was offered the chance to fill in. I called Russianoff for advice, because the only concerto I had worked on a lot was Copland, which didn’t seem right. Leon said to do Weber f minor. “I don’t have the music and have never played it,” I replied. Well, a phone call to Patelson’s later and the music was on its way. I learned the Concerto in about three weeks. Must have gone okay—Bartolomé Bover’s review in El Mundo said (my translation:) “As for the Concerto Number 1 in f minor of Carl Maria von Weber for clarinet and orchestra, the young clarinetist Kathleen Jones demonstrated a good technique in the virtuoso passages, pure style and great musicality in the Adagio and in the rest of the work, being much applauded.”

Another “oh, yeah”—that first season, the principal oboe (David Bourns,) myself, principal bassoon (Alan Brown,) and principal horn (Luis Arroyo) had the opportunity to play Mozart’s lovely Sinfonia Concertante for winds on November 12th with the PRSO. Samuel Cherson’s review in El Nuevo Día said, in part, (my translation:) “The group of soloists…demonstrated effective ensemble, cold elegance and skillful management of the virtuostic passages, above all in the last movement, Andantino con variaciones; the emotional and inspired slow movement was one of the high moments of the evening.”

My colleagues in the principal wind chairs were distinguished: flutist, Peter Kern, had been Kincaid’s last student at Curtis; David Bourns, oboist, had studied with Robert Bloom at the Manhattan School in New York; Alan Brown, bassoonist, was a student of van Hoesen at Eastman. They had all played in the Casals Festival Orchestras under the baton of the old man himself, and were impeccable instrumentalists, consummate musicians, and great gentlemen. They didn’t talk much in rehearsals—their playing, accurate as well as beautiful, gave me a space to fit into–rhythmically, harmonically and musically. I learned so much from them!

Like I said, there was plenty of playing for me to do. There were only two of us on contract then, myself, and Rafael Bracero, the second clarinetist. When we needed a bass clarinetist, UPR Professor Bob Handschuh, a fine player, joined us.

On my first day in the clarinet studio, a fellow had appeared and introduced himself as a CMPR June graduate, asking if we could play duets. I didn’t see any reason why not, so I found the complete Klosé and we picked out one of the duos to read. I was sight-reading; he played very well. I congratulated him, and he offered to help me if I needed anything. I gratefully accepted the offer and he took me to the airport to clear a trunk I had sent via cargo. I invited him to dinner as a thank you, and he picked out a quiet restaurant near the Conservatory, where we had an amiable meal. During the conversation he mentioned that he had played principal clarinet in the Puerto Rico Symphony during the previous season. My response (which I clearly remember) was “I hope they didn’t bring me in and kick you out of your job.” He replied, “No, no, I have no interest in the clarinet—it has always been so easy for me. I am going to conduct.”

Well, okay, I thought, fair enough. But, I would learn that the “I-have-no-interest” part wasn’t exactly true. He had, indeed, left the PRSO chair on his own volition; but he did want to continue playing in the great Casals Festival Orchestra in June. So, although on August 7th I had understood that I would be playing second clarinet, in the spring I was told I had misunderstood, and that I could play third on one work and assistant on another. I turned down the offer and asked for an audition. I was heard by Michele Zukovsky and Loren Glickman at Casals Festival time. There wasn’t much they could do for me, except extend the courtesy to hear me, which is all I asked for. I was plenty fizzed, but an older and wiser friend said “You just keep putting the bread on the table. Every day you get stronger.”

So that is a bit about my first year, which I mustn’t leave without talking about the delicious arroz con pollo (chicken and rice) con pegao (the rice stuck to the bottom of the pan,) and the alcapurrias, bacalaitos, y tostones (all wonderful fried goodies.) There were trips out to see the beauties of the island, like the road from Manatí to Juana Díaz, where around one curve you see the Atlantic to the north and the Caribbean to the south, and the gorgeous beaches of Luquillo, Mar Chiquita and Dorado. There was a catamaran with Captain Jack available for day trips from Fajardo out to nearby islets (like Icacos,) with fresh pineapple and fried chicken to refresh you after snorkeling. There was El Yunque, the only tropical rain forest in the United States. There was Old San Juan, with streets paved with blue bricks, brought as ballast by the Spanish galleons three centuries ago, dotted with old forts and surrounded by a wall, 40 feet high in places. So many new things to see, and I was playing in an orchestra and teaching—doing what I loved to do!